Growing ferns in water unveils a mesmerizing botanical practice where these prehistoric plants—survivors of epochs when dinosaurs roamed primordial forests—adapt to aquatic existence with surprising grace. This hydroponic approach transforms conventional houseplant cultivation into an elegant meditation on transparency, root architecture, and the fluid boundary between terrestrial and aquatic life. What emerges is not merely a survival technique but a revelation: ferns suspended in crystalline vessels become living sculptures, their root systems visible as intricate white networks mapping invisible pathways of nutrient absorption and growth.

My own journey into water-grown ferns began not with intention but accident—a Boston fern cutting placed temporarily in a glass vase while I searched for potting soil, forgotten for weeks, yet thriving with an enthusiasm that shamed my carefully tended soil-grown specimens. Those exposed roots, branching like river deltas in miniature, taught me that sometimes our most rigid assumptions about plant care deserve questioning. Water culture, far from being a temporary stopgap, revealed itself as a legitimate, even superior cultivation method for certain fern varieties, offering unprecedented control over nutrition while eliminating the variables and uncertainties of soil-based growing.

The Philosophical Foundation: Understanding Ferns’ Aquatic Adaptation

Before we immerse ourselves in practical methodology, we must first comprehend the botanical mechanisms that allow these ancient plants to transition from terrestrial to aquatic existence—a transformation that speaks to ferns’ remarkable evolutionary flexibility.

The Root Architecture Revolution

Ferns evolved their root systems over 360 million years ago, developing structures designed primarily for anchorage and water absorption rather than the complex nutrient extraction mechanisms of flowering plants. This relatively simple root anatomy makes ferns surprisingly adaptable to hydroponic conditions. Unlike many terrestrial plants whose roots suffocate without oxygen-rich soil, certain fern species develop specialized aquatic roots when grown in water—thinner, more extensively branched structures optimized for extracting dissolved nutrients directly from liquid medium.

These hydroponic roots differ structurally from their soil-grown counterparts. They lack the dense root hair networks that soil-grown roots depend upon, instead developing smooth, elongated structures that maximize surface area for nutrient absorption while minimizing oxygen requirements. This adaptation occurs within weeks of transitioning a fern to water culture, demonstrating these plants’ remarkable phenotypic plasticity—their ability to modify physical structures in response to environmental conditions.

The Oxygen Paradox

The most critical factor in water-grown fern cultivation involves dissolved oxygen. Roots require oxygen for cellular respiration—the metabolic process that powers growth and nutrient uptake. Stagnant water quickly becomes depleted of oxygen, causing root suffocation and eventual plant death. This explains why simply placing a fern in water doesn’t guarantee success; we must engineer conditions that maintain adequate oxygen levels throughout the root zone.

Water holds far less oxygen than air—approximately 8-10 milligrams per liter at room temperature compared to 21% oxygen content in atmospheric air. This concentration decreases as water temperature increases, creating seasonal challenges in warmer months. Successful water culture requires either frequent water changes that reintroduce dissolved oxygen or active aeration systems that continuously oxygenate the root environment.

Nutrient Delivery in Liquid Medium

In soil, complex ecosystems of microorganisms break down organic matter, slowly releasing nutrients in forms plants can absorb. Water culture eliminates these intermediaries, requiring us to provide nutrients in immediately available forms. This represents both challenge and opportunity—challenge because we must understand plant nutritional requirements with precision; opportunity because we gain unprecedented control over what our ferns receive, when, and in what quantities.

The Sacred Vessels: Selecting Fern Varieties and Containers

Not all ferns adapt equally to water culture. Success begins with selecting varieties whose natural characteristics predispose them toward aquatic existence, paired with vessels that support rather than hinder their adaptation.

Fern Varieties That Embrace Water Life

Boston Fern (Nephrolepis exaltata): Perhaps the most forgiving water-culture candidate, Boston ferns develop robust aquatic root systems with minimal transition stress. Their naturally high water requirements make them predisposed to hydroponic cultivation. I’ve maintained Boston ferns in water for years, watching them achieve sizes that rival their soil-grown relatives while displaying superior pest resistance and more consistent growth.

Maidenhair Fern (Adiantum species): These delicate beauties, notorious for dying dramatically in soil due to inconsistent moisture, paradoxically thrive in water culture where humidity remains constant and roots never experience drought stress. Their fine-textured fronds create ethereal compositions when paired with transparent vessels.

Kangaroo Paw Fern (Microsorum diversifolium): This Australian native adapts readily to water growing, producing thick, glossy fronds that emerge from rhizomes floating partially submerged. The architectural quality of its growth habit creates striking visual interest.

Bird’s Nest Fern (Asplenium nidus): While slower to adapt than other species, established bird’s nest ferns can transition to water culture, their central rosette creating dramatic focal points in large glass containers.

Java Fern (Microsorum pteropus): Originally an aquatic aquarium plant, Java fern represents the gold standard for water culture, having evolved specifically for submerged or semi-aquatic conditions. It tolerates low light and variable conditions with remarkable resilience.

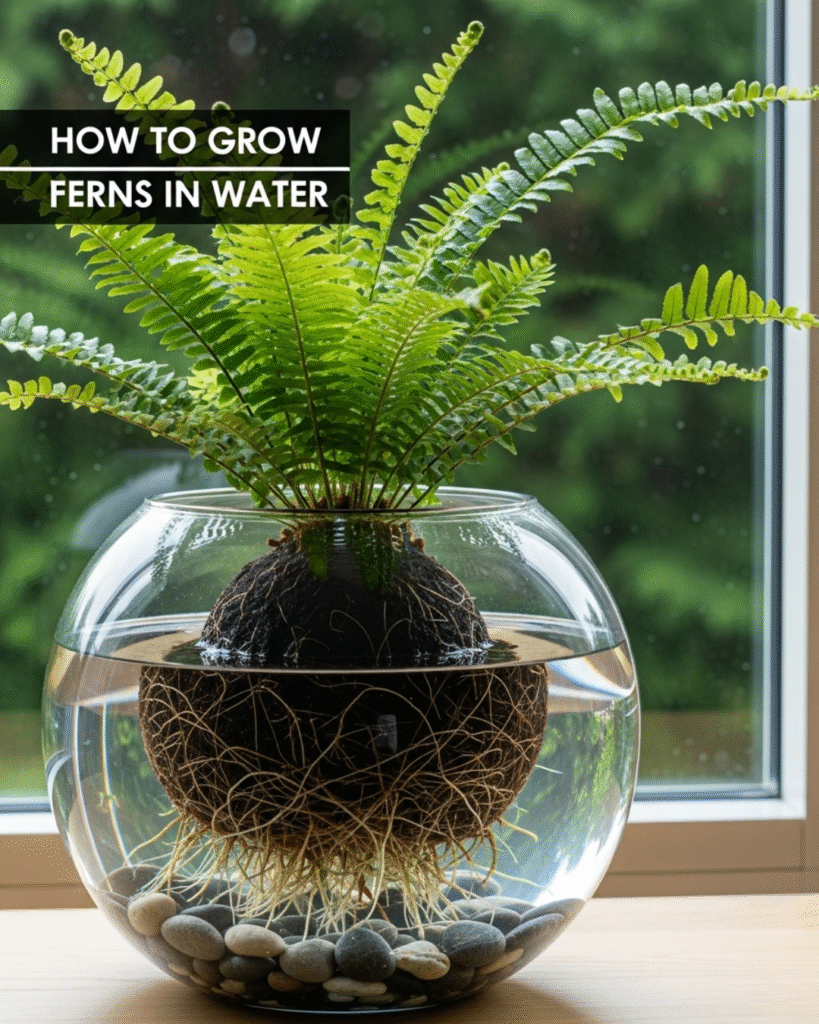

Container Selection as Aesthetic and Functional Choice

The vessel housing your water-grown fern serves dual purposes—functional support system and aesthetic frame that showcases the plant’s hidden architecture.

Transparent glass containers reveal the root system’s intricate beauty while allowing you to monitor water levels, root health, and potential algae growth. Select vessels with openings wide enough to accommodate the fern’s root ball while providing stability against toppling. Mason jars, decorative vases, laboratory glassware, and purpose-built hydroponic planters all serve admirably.

Opaque ceramic or colored glass prevents algae growth by blocking light penetration but sacrifices the visual drama of exposed roots. These work well for larger ferns where stability becomes paramount, or in bright locations where algae would otherwise proliferate.

Size considerations: Choose containers that allow 2-3 inches of clearance around the root system. Too large creates excessive water volume that stagnates; too small restricts root development and requires frequent water additions as evaporation occurs.

Stability architecture: Top-heavy ferns in narrow-based containers topple easily. Select vessels with wide bases or add decorative stones to the bottom for ballast. Some growers use specialized hydroponic net cups suspended in larger containers, separating the crown from direct water contact while allowing roots to dangle freely.

The Initiation Ritual: Transitioning Ferns to Water Culture

The moment of transition from soil to water represents a vulnerable threshold where careful technique determines success or failure. This process demands patience, gentle handling, and respect for the trauma we’re asking these plants to endure.

Step 1: The Liberation from Soil

Remove your fern from its pot with care, supporting the root ball to prevent crown damage. Gently shake away loose soil, then submerge the root system in room-temperature water, swishing gently to dislodge remaining dirt. This washing process requires thoroughness—soil particles decomposing in water culture create bacterial blooms that cloud water and compromise root health.

For stubborn soil clinging to roots, allow the root ball to soak for 20-30 minutes, softening the medium for easier removal. Work patiently, teasing apart roots rather than forcing them. Some root damage is inevitable; accept this as part of the transition cost.

Step 2: The Root Assessment

Examine the cleaned root system with critical attention. Healthy roots appear white to light tan, firm when gently squeezed, with visible growing tips. Remove any brown, mushy, or foul-smelling roots—these are dead or dying and will only contaminate your water culture. Use clean, sharp scissors, making decisive cuts rather than tearing.

This pruning, while seeming harsh, actually benefits the plant. Removing dead tissue prevents it from becoming a substrate for pathogenic bacteria while encouraging the fern to generate fresh, hydroponic-adapted roots.

Step 3: The Placement Ceremony

Fill your chosen vessel with room-temperature water—never cold tap water straight from the faucet, as temperature shock and chlorine stress the plant. If using municipal water, allow it to sit overnight so chlorine dissipates, or use filtered or distilled water.

Position the fern so the root system submerges completely while the crown—the point where fronds emerge—remains above the waterline. This distinction proves critical. Submerged crowns rot rapidly; exposed roots desiccate and die. The ideal configuration suspends roots in water while keeping the crown dry and exposed to air.

For ferns with substantial root systems, you may need to support the plant using specialized hydroponic collars, foam inserts cut to fit the container opening, or creative solutions like crossed chopsticks that the crown rests upon.

Step 4: The Patience Protocol

Newly transitioned ferns experience shock—wilting, yellowing fronds, and apparent decline. This is normal, expected, and temporary. The plant is shutting down its soil-adapted roots while generating new water-culture roots, a process requiring 2-4 weeks.

During this vulnerable period, maintain consistent conditions: moderate indirect light, temperatures between 65-75°F, and high humidity around the foliage (mist daily or place near a humidifier). Change water every 3-4 days, ensuring continuous oxygen availability while removing metabolic waste products the roots excrete.

Some fronds will die—accept this as the plant reallocating resources toward root regeneration. Don’t fertilize during this initial period; stressed plants cannot utilize nutrients and may experience fertilizer burn from accumulated salts.

Advanced Cultivation: Optimizing Water-Grown Fern Health

Once your fern establishes its aquatic root system—evidenced by new frond growth and healthy white root tips—you enter a refined phase of cultivation where subtle adjustments yield dramatic improvements in plant vigor and appearance.

The Nutrient Choreography

After the initial 3-4 week establishment period, begin introducing diluted liquid fertilizer. Use hydroponic-specific formulations designed for water culture, or dilute conventional liquid houseplant fertilizers to one-quarter the recommended strength. Ferns are light feeders compared to flowering plants; over-fertilization causes more problems than under-fertilization.

I employ a feeding schedule of weekly applications during active growth (spring and summer), reducing to every two weeks during dormant periods (fall and winter). The water should remain clear; cloudy water indicates over-feeding or bacterial blooms requiring immediate water change.

Fertilizer composition matters profoundly. Ferns require balanced nutrition with special attention to micronutrients, particularly iron and magnesium. Deficiencies manifest as yellowing fronds with green veins (iron chlorosis) or general pallor and weak growth (magnesium deficiency). Hydroponic fertilizers typically contain these trace elements; conventional fertilizers may not, necessitating supplementation.

The Water Exchange Ritual

Change water completely every 7-10 days, more frequently in warm weather or if algae appears. This regular exchange prevents salt accumulation from fertilizers, removes root exudates that can inhibit growth, and refreshes dissolved oxygen levels.

During water changes, gently rinse roots under lukewarm running water, removing any algae or debris. Inspect root health, trimming any brown or damaged sections. This regular interaction creates intimate familiarity with your plant’s condition, allowing you to detect problems before they become crises.

Water quality considerations: Tap water varies dramatically in mineral content and pH. Hard water, high in calcium and magnesium, can cause nutrient lockout where pH elevation prevents roots from absorbing iron and other micronutrients. If your ferns display chronic yellowing despite fertilization, test your water’s pH. Ferns prefer slightly acidic conditions (pH 5.5-6.5). Adjust using pH down solutions designed for hydroponics if necessary, or switch to rainwater, distilled water, or filtered water.

The Light Dialogue

Water-grown ferns generally require less intense light than their soil-grown counterparts, as they’re unable to recover from light stress as readily without soil’s buffering capacity. Position them in bright, indirect light—near east or north-facing windows, or several feet back from south or west exposures.

Direct sunlight heats water, reducing dissolved oxygen while potentially cooking roots. It also accelerates algae growth, creating green water that blocks light from roots and competes for nutrients. If algae becomes problematic, reduce light intensity, change water more frequently, or switch to opaque containers.

The Humidity Embrace

Ferns evolved in humid environments—forest floors, stream banks, tropical canopies where atmospheric moisture remains constantly high. While water culture ensures roots never experience drought, fronds still lose moisture through transpiration. Low humidity causes crispy leaf margins, browning tips, and overall decline.

Maintain 50-70% relative humidity around your water-grown ferns through grouping multiple plants (their collective transpiration creates microclimates), using pebble trays filled with water beneath containers, regular misting, or employing humidifiers. In dry winter months when heating systems desiccate indoor air, supplemental humidification becomes non-negotiable for maintaining healthy fronds.

Troubleshooting: When Water Culture Challenges Emerge

Even carefully tended water-grown ferns occasionally display distress signals. Learning to read these botanical messages and respond appropriately transforms frustration into deepened horticultural understanding.

Root Rot Despite Water Culture

Symptoms: Brown, mushy roots with foul odor; declining frond health despite apparently adequate conditions.

Diagnosis: Insufficient oxygen in water, often caused by stagnant conditions, excessively warm water, or bacterial overgrowth.

Solution: Immediately change water, trim all affected roots, and implement more frequent water changes. Consider adding an aquarium air stone connected to a small pump—the continuous bubbles oxygenate water while creating gentle circulation. Reduce fertilizer concentration, as excess nutrients feed bacterial populations. If problems persist, start fresh with clean water and sterilized container.

Algae Invasion

Symptoms: Green water, slimy growth on container walls and roots, sometimes foul odor.

Diagnosis: Excess light reaching water combined with nutrients creates ideal conditions for algae proliferation.

Solution: Reduce light exposure or switch to opaque containers. Change water more frequently, thoroughly cleaning container and rinsing roots during changes. Reduce fertilizer strength—algae thrives on the same nutrients your fern needs. Some growers wrap containers in aluminum foil or fabric to block light while maintaining airflow.

Moderate algae doesn’t harm ferns directly but competes for nutrients and oxygen while creating unsightly conditions. Severe blooms can suffocate roots and introduce pathogens.

Frond Yellowing and Decline

Symptoms: Progressive yellowing from oldest to newest fronds, slow growth, general decline.

Diagnosis: Multiple potential causes—nutrient deficiency (most common), insufficient light, root system problems, or natural aging.

Solution: Evaluate systematically. Check roots—if healthy and white, increase fertilizer concentration gradually. Assess light—move to brighter location if currently in deep shade. Examine water change frequency—irregular maintenance causes nutrient imbalances. If oldest fronds yellow while new growth appears healthy, this represents natural senescence requiring no intervention beyond removing dead fronds.

Crown Rot Catastrophe

Symptoms: Blackening where fronds emerge, mushy crown tissue, fronds collapsing at base.

Diagnosis: Water level too high, keeping crown constantly wet.

Solution: If caught early, remove all affected tissue with sterilized blade, cutting back to healthy growth. Lower water level so only roots submerge. Apply cinnamon powder (natural antifungal) to cut surfaces. Increase air circulation around the plant. Severely affected plants may not recover—crown rot often proves fatal.

Mineral Buildup and Salt Accumulation

Symptoms: White crusty deposits on container walls, at water line, or on roots; leaf tip burn.

Solution: More frequent water changes, reduced fertilizer concentration, or switching to lower-mineral water sources. Thoroughly scrub containers during changes to remove deposits before they concentrate further.

Maximizing Success: The Holistic Approach to Water-Culture Ferns

Exceptional water-grown ferns result from viewing cultivation holistically—understanding how temperature, humidity, light, nutrients, and even aesthetics interact to create thriving plant ecosystems.

Seasonal Rhythms in Water Culture

Even indoors, ferns respond to seasonal changes—day length variations, temperature fluctuations, and humidity shifts. Honor these rhythms rather than fighting them.

Spring awakening: As days lengthen, ferns enter active growth. Increase fertilizer frequency, change water more often as plants uptake nutrients faster, and watch for rapid root growth that may require larger containers.

Summer abundance: Peak growth occurs now. Monitor water levels carefully—increased transpiration can dramatically lower water in containers within days. Ensure adequate humidity as air conditioning desiccates indoor environments.

Autumn transition: Growth slows as days shorten. Gradually reduce fertilization frequency, preparing plants for winter dormancy. This is ideal timing for propagation projects while plants remain vigorous.

Winter rest: Most ferns enter semi-dormancy—growth stalls, nutrient uptake decreases. Reduce fertilizing to monthly or eliminate entirely. Water changes can extend to every 10-14 days. Monitor for dry air problems from heating systems.

Propagation Possibilities

Water culture facilitates easy fern propagation. Many ferns produce offsets or plantlets that can be separated and established in their own containers. Boston ferns generate runners with baby plants; bird’s nest ferns produce pups around their base. Simply separate these with clean cuts, ensuring each division has roots attached, and place in individual water vessels.

Some ferns propagate from spores (the tiny dots on frond undersides), though this represents advanced cultivation beyond most water-culture practitioners’ interests. For simpler multiplication, division remains most practical.

Creating Living Art Installations

Water-grown ferns transcend functional houseplants to become living sculptures. Consider creative presentations:

Layered glass vessels where decorative stones, marbles, or crystals anchor the base while adding color and visual weight.

Laboratory glassware collections featuring ferns in beakers, Erlenmeyer flasks, and graduated cylinders create botanical-scientific aesthetic.

Suspended installations using macramé or wire holders allow ferns to float at eye level, their roots visible from all angles.

Grouped compositions combining multiple fern species at varying heights create verdant vignettes that transform corners into lush focal points.

Integration with Aquatic Ecosystems

Ambitious cultivators can integrate ferns into aquarium systems, where fish provide nutrients through waste products while water circulation ensures constant oxygenation. Java ferns particularly excel in these applications, often used in aquascaping to create underwater forests. The symbiosis between fish and plants creates self-sustaining ecosystems requiring minimal intervention.

Conclusion: The Liquid Garden Awaits

Growing ferns in water represents a departure from conventional houseplant cultivation into a practice that combines minimalist elegance with botanical fascination. These ancient plants, their roots suspended in crystalline vessels, become meditations on transparency, growth, and the unexpected adaptability of living systems.

The journey begins simply—a single fern, a glass container, and water—yet opens into endless exploration. Each root that branches, each frond that unfurls, each day the water remains clear and the plant thrives despite the absence of soil represents small victory over conventional assumptions about how plants must be grown.

Your water-grown fern garden awaits creation. Select a variety that speaks to you, gather a vessel that pleases your aesthetic sensibility, and begin the gentle process of transition. The first weeks require patience as your fern adapts, but soon you’ll experience the profound satisfaction of watching roots multiply in their transparent world, fronds emerging with renewed vigor, the entire plant thriving in liquid suspension.

This is cultivation stripped to essentials—plant, water, light, and your attentive care. Nothing more is needed, yet everything worth growing emerges from these simple elements. Begin today, and discover how ferns grown in water transform not just your plant collection but your entire understanding of what cultivation can become when we release attachment to how things have always been done and embrace what might be possible instead.